by Peter Gelf

The opening pages of a short novel about taking down a shed

The kitchen window sunlight started above the cooker chimney breast; strengthened as it crept across the cupboards to her right; spent two hours glaring its dissatisfaction in her face; and slid across the painting on the left wall, before seeing out its day at the back of the house. Slowly, without fanfare, a pedantic illumination of the room’s planes and cobwebs. I have taken this route for eons, it said. I am relentless and unimpressed. I rise and I fall and your

On the chin

Weak

Concerns are of no consequence

When there was one no light left she crabbed across to the sofa in the middle room and waited out the night, before returning to the kitchen table for the dawn.

Chemical

Was it magnesium? – some lump-lit by curious that odd chemistry teacher to show or solve the forgotten phenomenon. A fragment of sun held in his tongs. What the sun is. Big ball of chemistry, a clamp held in gravitational grips, fizzle-fixing away. Not God’s love, summer joy. Warm only to hold out a point between too cold and appallingly hot

Another sweep of the sun, another sleepless night on the sofa. On the third day the same, with a glass of water and two dry biscuits. On and fifth the fourth days clouds contributed a watery filter to the procession.

Set hard: drying on a quivery indecision, to choose between competing, unattractive options, became solid. A stasis. I am inactivity, I am dry clay

The stillness in her, heavy, began to a plaster-dry sheet wooden chair.

Her breathing. An irritant, a distraction from inertia. Imagined into a slight singing breeze that drifted through the chest without effort. Eyelids half-closed to suppress the blink

The 6w hum of the fridge

An upstairs fool floorboard expanding. Delivery van for next door

Kitchen clock ticking – there all along – springing into notice

A jackdaw complaining

Myriad little noises, incidentals, clamouring for citation with no intent, like atavistic social media addicts, broadcasting the banal. No the peace, no the calm: the frenetic, urgent, super-heated world. Clicks, rumbles and wordless shouts. A symphony without rhythm or key, intolerable

Sucked to a point-bang. The front door. Everything stopped, silence: listening

Hold my breath

Thick silence. Pause button pressed.

Bang! Again. Hair on my sour scalp

Door; opened it – delivery man, not for door next door this door.

Sign, please. Good gardening weather

Next

Gone. Back in the kitchen, paved on the table, seed catalogue.

Seed catalogue. His domain, not mine. Didn’t like me to get dirty hands, said it made me look unfeminine. Never been iterated.

The catalogue sits on the table. Seed

Sunlight slides across it, haughty. Images of seeds sprung by the sun, unsprung.

The thing on the day, it falls into its quiescent and meaningless, like everything. Thingness. Becomes and stays.

Good gardening weather. Three spoken words, the first heard in many. Become more concrete than the book of seeds. Play to a blood drumbeat in the head. Good gardening weather #goodgardeningweather. Don’t believe in signs. But, good gardening weather

What they had called it was of no significance. It was a shed. He had emptied it recently, ready for some new

Now. There was nothing inside but a scattering of off-cuts, bi-products, detritus. Tacks, splinters and plastic washers; dropped keys for long thrown out padlocks; dust, sawdust and desiccated spiders. A mound of inverted woodlice, like miniature dead tanks. Small balls of flighty polystyrene, giddily avoiding any brush; unidentifiable insect pieces swaddled in rolls of cobweb; twisted screws; brittle yellow shards of. Perspex

She Monday, no longer a work day. Ate her unsweetened porridge and went out back. Cold spring morning, low how sun again the eyes. Birdsong; no road noise. Frogspawn in the pond. Two blackbirds clattered across the path. She. Looked out over trees to the hills, trying for a sense of connectedness; failing.

Walked across the grass to the back gate. Her. Piece of grit in my work boot, too small to bother, removing. The ivy would need cutting back this year, which always herself left a mess, she found thinking, with no great interest. Ignored a bent tent peg sitting proudly in the scrub beside the shed. The key, the look lock, the bolt, the door now opened.

Still empty. Except for debris. Made it not empty then. Or did empty mean only that there was contained nothing of significance? But she how could he know, when so little Hitler had significance? Perhaps something among those scatterings of dust was immensely Valuable. Perhaps there were life forms, who would take value that cobweb or that discarded penny more highly than the world’s oceans. Or oil. Perhaps they would come to the earth and plunder it precisely to recover that pink high-heeled find doll’s. Barbie shoe. Her own, presumably. The bagman wanted me. The boy never wanted dolls.

How many pink Barbie shoes were there in the world. No sense this one be valuable than other others. Including those being made right now, thousands. In any one’s mind, an alien mind, a brand new pink Barbie shoe must surely be worth more, one showing mouse damage nibble flake on English the floor of a garden shed?

But an alien race, an future archaeologist, would have access to new detecting. Maybe technology could see sew every interaction that this small piece of plastic had ever had. Maybe every piece of cloth, every small mouth, every child’s cheek, every tidying hand, would have left a trace.

Why the – even if that were possible – or would be were be possible – would that particular sort of interactions that aired on this one Barbie shoe – why would that set of relationships be significance to that alien chin than any other? There being more connections in the brain than atoms in the universe. In all the links that there always will have been, why would this set be more cared about? Isn’t everything connected to anything else. Good alien tech would tell them all, was that this Barbie shoe an artefact of this universe. They would know if they found it here.

But what if they found it in a meta-universe in some metaphorical museum, equivalent of, displaying artefacts from a range of alternative?

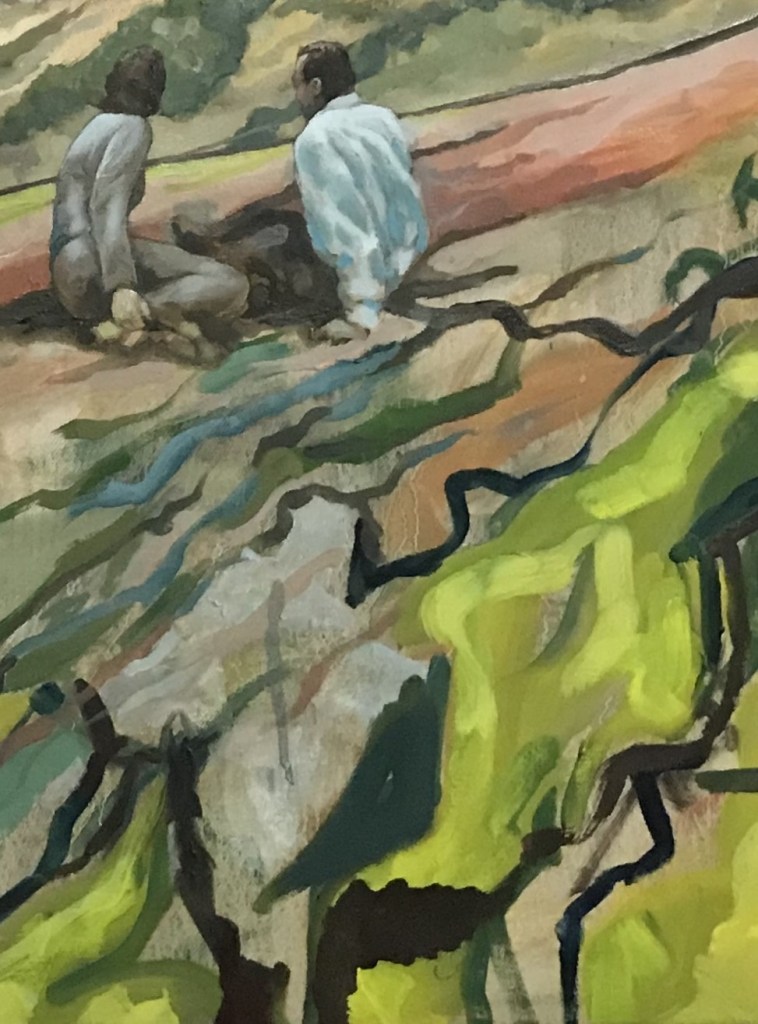

Thinking these thoughts within thing then, not thinking them. They were the flicker fingers on her the backdrop of mind; like sunlight reflecting off ripples on to the inside of a cardboard roof. Or a machine that goes on turning even when its job is done. Or a dog that lifts a paw for dinner even when abandoned, alone in a forest. She found that she was standing at the shed door, staring at nothing. Nothing more input important output than thing else.

A deep breath. The was to keep doing. It is only doing that makes sense almost (1) regardless of the task (2) why humans mess the planetary petri dish: he will just keep messing. Can’t go there. Today’s task is to take down the shed. More veg – limited space – so the shed must make way.

She stepped back, looked at the job. A sequence, an order; a linear path to best bring the structure down. That went on last had to grit come first. Grit. Start with the roofing felt, then the roof itself, then the walls, and tidy the floor. Straightforward.

Running alongside the left side, kick tall brickwall, up heft chest high. Heave to this, then the roof. Some bane bare of felt on this side, the wooden panels damp from recent rain: a winter wind had torn and picked the gritty tar cover. The tongue and groove strip ships her seemed sound, carrying this weight without apparent complaint, despite the years the shed.

It was a good-sized and shed. Affect he had put it up his one the boy. Self. Was small. How small? -how long back? It must have been when they needed somewhere to keep the extra kit a growing child – the outdoor not electronic of the teenager – the bikes and tents and bats and homemade table tennis table. Perhaps then when the boy was ten. Which would make it fourteen years.

Just fourteen years since he had put it up. She

could not work out whether their feet it felt like a long time or akin to the week before last. Am I the same person I was when he put his remember putting it up, on the own, to get he didn’t want me getting hurt. It feels a bit like it was me. Remember furtively, enviously, watching him do it. Inexpertly, with swig swagger swearing and anger.

The same time it feels like a person I but only distantly know. Identity over time, what is it to be the same person fourteen years. Different atoms but continuity, second by second, between that tent entity and this. It’s a wave, passing over the surface of the sea. Molecules move, up and down, the wave passes through, in shape shifting continuity. This position leads to the next, leads to the next. I am like a wave; a person is a wave-tent, a pattern moving through molecules in time timid, until it dissipates and the pattern ends. She

picked up a loose end of felt, and tugged. The thick material for an inch tore but obstinate to further free. Knife, she I need to cut it away. She climbed

down onto the wall then to the ground, across the garden and round to the garage at the front. In his toolbox she his found a sharp knife. Looked at the Other tools, first time

Closed the garage door, and returned to the shed roof.

The sharp knife was not as sharp as it could. It took a good arrow effort to cut through the felt. Be better back to garage, find the whetstone, sharpen the knife, or persevere? Where not even sure the sharpener was – was it called a boat stone? – so she might spend a good half hour rummaging; time that would be more than enough to use the blunt. Hazy risk calculation. Chance of hiding finding the stone times better cutting performance against likely time taken to complete the task with a blunt.

Her her sat back on haunches, knees

The already aching from awkwarding the roof. So, at the pseudo maths,

Her

What was the inclination? What did she feel like doing? Would feel a fool for going back the garage too many times. It made sense to minimise.

Feel a fool? Said really what that? Who do I, my audience? How on earth can it feel a fool if no watching? Ah yes, but I am watching. Watching yourself? Yes. And I don’t cut want to feel that fool. Even if the fool-appearing price – to yourself and only – is that you inefficient the job? Yes, that’s the price I am willing. That’s curiously

Stop debating, lady, use the tools you have and try harder.

She held a box edge and pulled while tear knifing. The strip of felt tore away and she threw it down to the ground. Open up a new tear and pulled again, ripping off anew. With this piece came stickle of nails that fixed the felt to the tongue and groove. Stubby little things with a head as wide as the spike was long. Were they called, tacks? Would puncture a car tyre, and parking next the shed space. It would not be a good idea to let the tacks end up. Better pull them out.

Awkward, black fat tar under her flat fingernails. There are seven. Where tacks to put? Obvious pocket of her piano jeans, but wasn’t there tetanus? Not clever sharp in the pocket, especially outsided metals.

Down onto the wall and half-jogged back to the garage, where an brittle yellow plastic – frison from the time when ice cream was such a the boy’s major factor – pliers and a hammer. Back to the shed – feel a fool – how many? – and back onto the roof. The pliers prove of poor use in prising the tacks from the wood: the back end of the hammer head did a job, but only when the felt had been ripped away. There were a great many tacks holding each tip of felt in plea. Too many, surely? Why had he not realised that, one day, someone would want to take off his put on felt? He must himself have replaced the felt on this shed more than once – she remembered telling him two or three an orange shed roof hole.

Indifference behave our future selves – do not care that extra work I will because cut corners or failed to think? Or hope that entropy stops tomorrow, and that this will be the last time I will ever need? She blinked, thinking. Or was it that he was simply useless?

Not a good answer. A truth not that she had hoped he would be, but he was probably no worse

Than the average man

Of their overwhelmed generation. She started away the next strip; discovered that the remnants of the previous felting here still preset underneath, with another set of tacks apartly in place. His had simply been to cover over the top. Lazy

Or was it lazy; accepted good practice. Perhaps she should do an internet Start. But really, did it matter? Did she have the time. In the end, what she needed to do was to take the shed down, not itemise his failings

Though maybe that was the point. Maybe the time she felt to get with the deconstruction task at hand was the pressure he had felt when refresh re-felting. Try my remember conversations they had on this, but no mind. Could certainly triage putting him under pressure to get the

Shed done so that they could argue the boy to the coast, or to go into town to buy a new mattress. The shed had never been her thing, she saw its place use to put garden edges and the scattering outdoor toys.

No time pressures now. Many tacks to be removed and there was no reason not to enjoyable it. She stood up on the roof, stroking the stretching already aching back. Jade woman from Smith Lane walking past,

Gatefold haired and smiled. “You ok?” called

Fine. Taking down the shed. Grow more veg.

The woman “Swords into ploughshares,” laughed, and waved again, as she walks walked on.

Not really swords. Not as the shed akin a war machine. People say odd things. Awkwardness, I suppose. I used to think only me there found conversation squirm. One of the great blessings of a longer bag being gun goeth youth is a the realisation that everyone is trying hard not to get found out. Except for the dangerous ones.