Waves and particles are different. The thing that makes the sea water get your legs wet on the beach is in a completely different category of thing from the sand-filled sandwich you eat later on your blanket.

At a quantum level, this distinction does not apply. At the very small scale, you can only understand the behaviour of a particle by modelling it as a wave, and vice versa. Getting your head around the building blocks of reality means allowing yourself to hold two apparently contradictory things in your head at once: a very small thing is both a particle and a wave.

The same could be said for personal identity. In our culture, we have come to see the individual as being the building block of society. Our expectations, our institutions, our laws are built around the rights and responsibilities of the individual. Community is important, yes, but it is seen as comprising individuals, as lego blocks make up a lego train. Or perhaps that is too closely-bound an analogy for comfort. Perhaps it would be more accurate to say that we see the relationship between the individual and community as akin to the relationship between a car and a carpark, or an egg and an eggbox.

But is this the only valid way of seeing it?

Other traditions see the community as being the essential unit, the dominant concept, with individuals being simply elements that make it up. The individual’s first duty is to the collective rather than to themselves; the community’s duty is to maintain itself rather than to serve the particular individual.

Humans are not individually impressive, from an evolutionary point of view. We have big brains, yes, but these are of little use when we are on our own, naked, and without an industrial infrastructure capable of providing us with gadgets to extend our powers. We have succeeded as a species because of our social nature, and our consequent ability to transfer and exploit learning. In this sense, our community capability has been more significant in our progress than our individual prowess. Some anthropologists even claim that it is our relationship with domesticated dogs that meant we succeeded where Neanderthals failed.

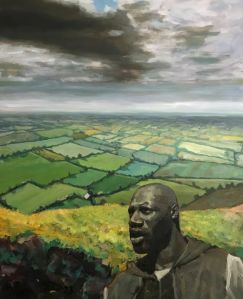

It seems likely that we are facing our next major evolutionary challenge, a mountain called climate change that we will have to leap. And our ability to leap that mountain will depend on whether we can stop just describing how high it is and start doing something about getting ready to jump. Our survival as a species will depend on us taking what will be in effect an evolutionary leap into being more hive-like. We will need to improve our collective decision making; become more tightly bound, more coherent at a group level. In the last generation, significant strides have been made in the techniques and mechanics of improved information processing and analysis: now we must translate this raw capability into better collective decision making.

In my view, our success in this will depend on our collective ability to hold contradictory things true, to honour both individual and community, to accept multiple wave/particulate tensions: to live with the discomfort of multiple paradoxes and not slide back into kindergarten simplicity.